Strongyloides

Strongyloides are important parasites

Soil-transmitted helminths, such as Strongyloides nematodes, are estimated by the WHO to infect 1.5 billion people globally as well as causing substantial loss to livestock practices. Around 600 million people are infected with Strongyloides parasites - Strongyloides stercoralis and S. fuelleborni. Two species, S. ratti and S. venezuelensis, are natural parasites of rodents and are used as laboratory models for studying Strongyloides parasitism, and nematode parasitism more generally.

Strongyloides ratti - adult parasitic female

Adapted from Hunt et al (2016) Nature Genetics 48 299-307

The Strongyloides life cycle has genetically identical parasitic and free-living stages.

Third stage infective larvae (iL3) are female only and infect their host by directly burrowing through the skin of their host, eventually establishing as adult parasites in the mucosa of the small intestine. Eggs pass out of the host via the faeces, develop directly into iL3s and seek out a new host or develop into free-living adults (male and female), the offspring of which develop into iL3s. Because the parasitic adult is female only and reproduces by parthenogenesis, the Strongyloides life cycle includes genetically identical parasitic and free-living adult female stages. Comparison of these two life cycle stages, particularly at a genetic and molecular level, can provide insight into the differences between being a parasite and being free-living, allowing us to directly address questions about the genes and proteins these nematodes require for parasitism.

S.ratti is an excellent model system for studying the molecular and genetic basis of parasitism because:

-

Quality genomic data: The S. ratti genome is assembled into two autosomes and an X chromosome in two scaffolds.

-

Genetically identical parasitic and free-living adult stages: Because the parasitic and free-living stages are genetically identical, differences in the life styles of the two adult stages must therefore be due to epigenetics. Strongyloides is well suited as system for investigating questions about parasitism because we can make direct comparisons between these two life cycle stages. This is an almost unique feature amongst nematode life cycles.

-

Transgenic techniques: Strongyloides is leading the field when it comes to genetic manipulation techniques in parasitic nematodes. For example, they were the first and are now one of only a few parasitic nematode species that CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully used for.

Caenorhabditis inopinata

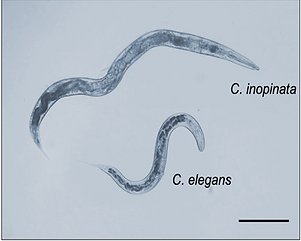

Caenorhabditis inopinata is the closest known relative of C. elegans. There are many genomic and genetic similarities between C. inopinata and C. elegans, yet these two species differ in a number of ways including, morphology (C. inopinata is around twice the size of C. elegans) and ecology (C. inopinata is vectored between live fig fruits by a fig wasp; C. elegans inhibits fallen, rotting fruits).

We have sequenced the genome of C. inopinata and demonstrated that lab-based techniques used for C. elegans including RNAi, CRISPR also work in C. inopinata, as well as lab culturing methods similar to those used for C. elegans.

C. inopinata life cycle. C. inopinata is vectored by a fig-pollinating wasp which has a mutualistic relationship with F. septica figs. The nematodes multiply inside the fresh figs and when the wasps emerge from the fruit as adults and disperse to new fig trees, nematodes are transferred to fig fruits during wasp oviposition.

From Kanzaki et al (2018) Nature Communications 9 3216